This fact box will help you to weigh the benefits and harms of a surgery of the knee joint (arthroscopy) for osteoarthritis of the knee. The information and numbers in this fact box represent no final evaluation. They are based on the best scientific evidence currently available.

This fact box was developed by the Harding Center for Risk Literacy.

Osteoarthritis in the knee occurs when the cartilage on the ends of the knee bone wears down over time and causes damage to the knee joint. Osteoarthritis is the most common joint disease and occurs more often in older people [1].

There are many different factors that can contribute to osteoarthritis of the knee (e.g., being overweight or prolonged strain to and overexertion of the knee joint). At advanced stages of the disease, the cartilage can wear down completely (cartilage degeneration) along with other joint tissues. Symptoms of osteoarthritis include feelings of tension, limited mobility in the joint, and pain when resting and during exertion later during the course of the disease [1].

During knee joint surgery (arthroscopy), fine tubes are inserted through a small incision into the knee under local or general anesthesia. Fluid is then injected into the knee to flush loose tissue and cartilage particles out of the knee joint. This procedure is called lavage. The smoothing of mechanically rough cartilage surfaces and the removal of detached cartilage parts is called debridement [1, 2].

Adults who suffer from severe knee pain and joint problems (e.g. restricted mobility).

Non-surgical (conservative) treatments include lifestyle changes (e.g., exercise, weight loss), surface treatments (e.g., physical therapy), pain medication, and steroid injections. Steroid injections involve injecting a corticosteroid (such as triamcinolone, hydrocortisone, or methylprednisolone) directly into the affected joint (intra-articular injection). The active substance is supposed to have an anti-inflammatory, decongestant, and thus pain-reducing effect [3].

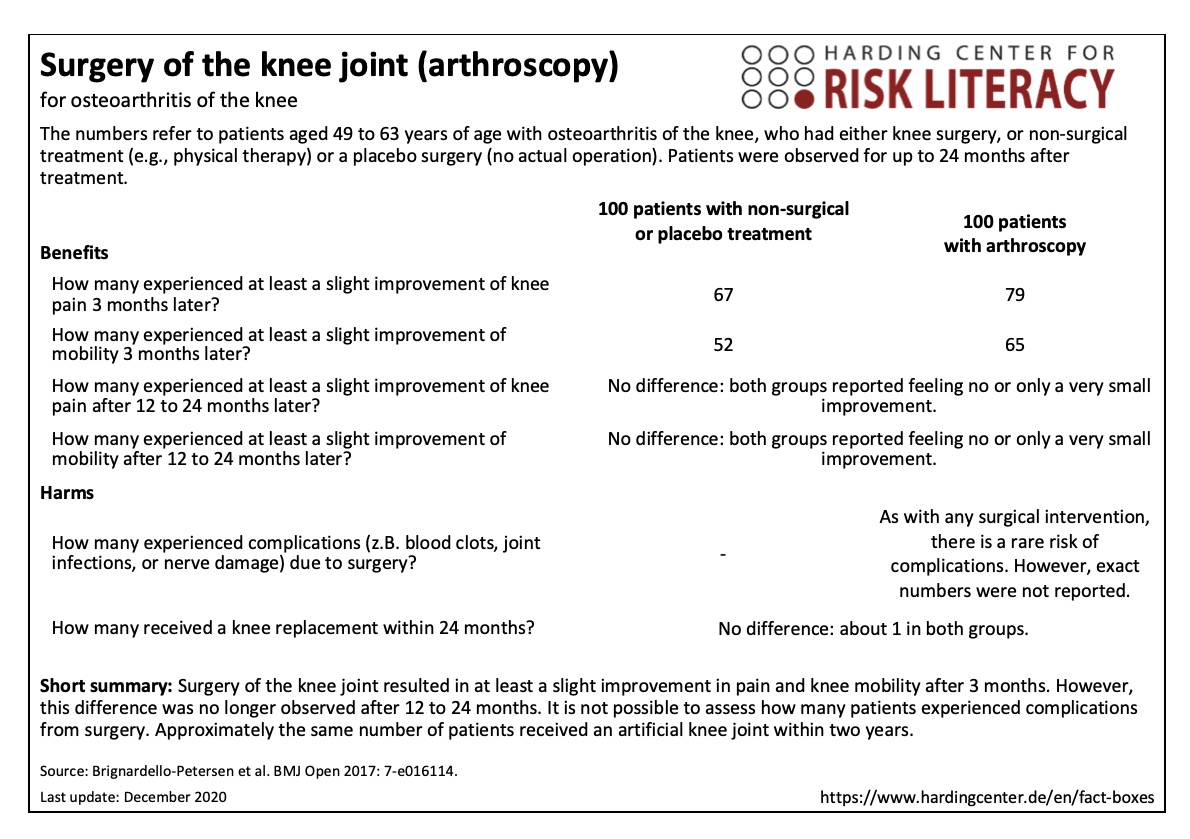

The fact box compares knee joint surgery (arthroscopy) with placebo surgery or non-surgical treatment regarding their benefits and harms. Non-surgical methods include, for example, lifestyle changes through exercise, weight loss, and physical therapy, as well as pain medication and steroid injections. Patients were observed for up to 24 months.

The table may be read as follows:

79 out of every 100 patients felt at least a slight improvement of pain after the knee joint surgery. This was also the case for 67 out of every 100 patients with non-surgical or placebo treatment. Thus, arthroscopic knee surgery was associated with a slight improvement of pain for about 12 out of every 100 patients during the first three months after treatment.

In both groups, one out of every 100 patients received an artificial knee joint replacement within 24 months after the treatment [2].

The numbers in the fact box are rounded. The numbers for the pain outcomes are based on 9 studies with a total of 1,102 participants. The numbers for knee mobility outcomes are based on 6 studies with a total of 835 participants. For knee replacement, the numbers are based on data from 2 studies with a total of 497 participants [2].

The phrase “at least a slight improvement” relates to a 100-point scale on which patients were asked to indicate their pain and mobility of the knee before and after treatment. In order to measure the difference between treatments, it is common in clinical research to average the scores before and after treatments, and then to compare both values with each other. The smallest average improvement was determined to be 12 points on the 100-point scale and was labelled “at least a slight improvement.”

The at least slight improvements of pain and mobility during the first three months were no longer observed after twelve months [2].

As with any surgical intervention, arthroscopy is associated with the risk of surgical complications (e.g., blood clots, joint infections, or nerve damage). However, the results reported in the studies were not sufficient to assess the risk of complications for this intervention exact numbers on the risk of complications [2].

| Alter von 18-29 Jahren | Alter von 30-75 Jahren | Alter ab 75 Jahren | |

| Frauen | - | X | - |

| Männer | - | X | - |

Erklärung der Symbole: X = für diese Personen gelten die Zahlen in der Faktenbox; (X) = auf diese Personen lassen sich die Zahlen unter Vorbehalt anwenden (in solchen Fällen ist eine Rücksprache mit ärztlichem Personal empfehlenswert); - = für diese Personen gelten die Zahlen nicht; ? = es ist unbekannt, ob die Zahlen für diese Personen gelten

The evidence was assessed by the authors of the review included. According to their assessment, the evidence is of overall moderate to high quality, depending on the benefit or harm in question: some of the results might change through further research (moderate evidence), while for others it is very unlikely that they will be changed through further research (high evidence) [2].

- December 2020 (update of the research, no new evidence; update of the accompanying text)

- July 2019 (update of the accompanying text)

- October 2018 (creation)

Information within the fact box was obtained from the following sources:

[1] IQWIG. Arthrose 2018. Available at: https://www.gesundheitsinformation.de/arthrose.2700.de.html (15.12.2020.)

[2] Brignardello-Petersen R, Guyatt GH, Buchbinder R et al. Knee arthroscopy versus conservative management in patients with degenerative knee disease: a systematic review. BMJ Open; 2017: 7-e016114. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016114.

[3] Jüni P, Hari R, Rutjes AWS, et al. Intra-articular corticosteroid for knee osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015(10). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005328.pub3.